CBC Anne-Marie takes the CBC on an architectural tour

Anne-Marie recently sat down with the CBC to discuss Canadian architecture — come along the tour with us!

—

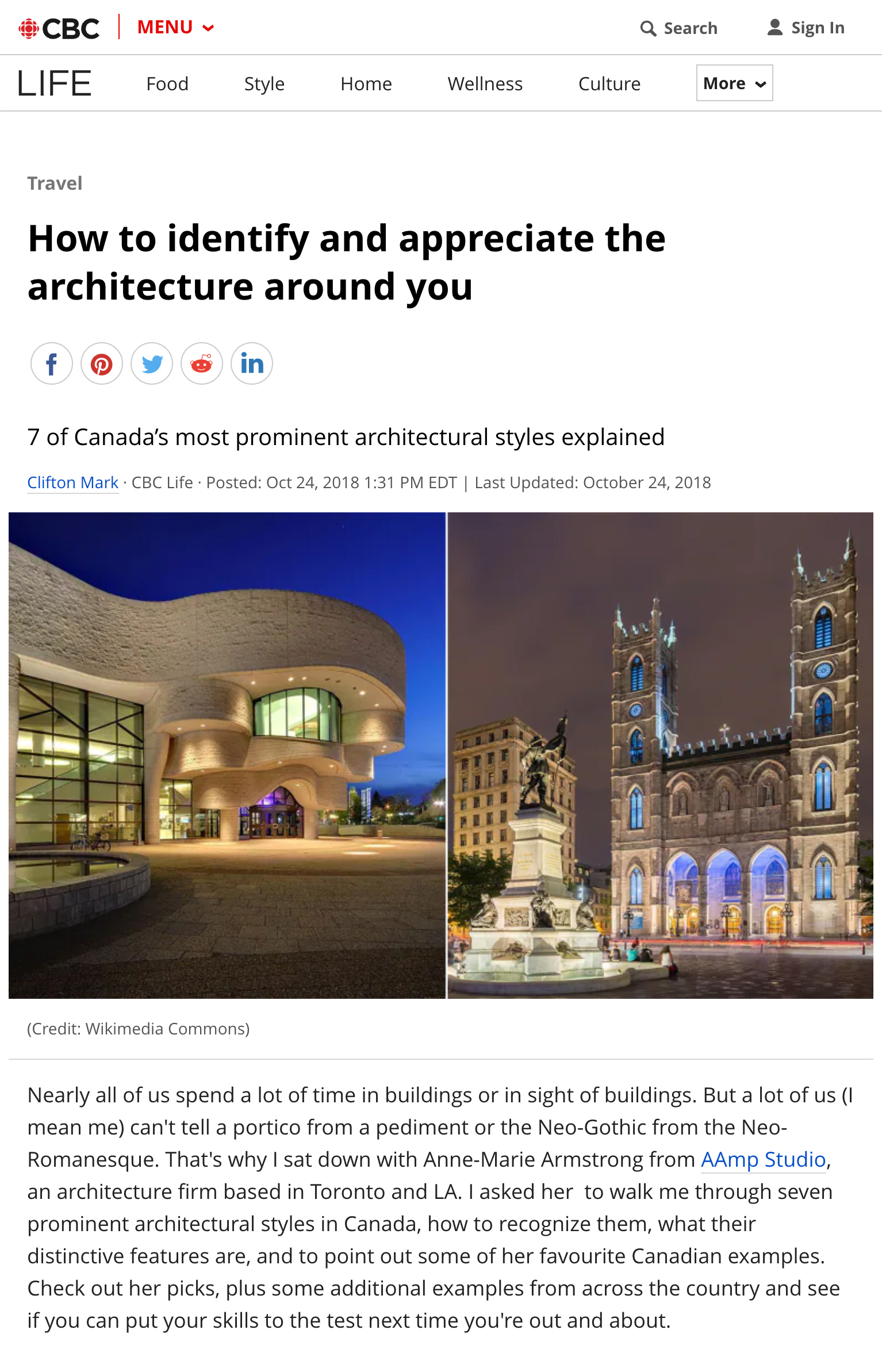

How to identify and appreciate the architecture around you

7 of Canada’s most prominent architectural styles explained

By Clifton Mark

Nearly all of us spend a lot of time in buildings or in sight of buildings. But a lot of us (I mean me) can’t tell a portico from a pediment or the Neo-Gothic from the Neo-Romanesque. That’s why I sat down with Anne-Marie Armstrong from AAmp Studio, an architecture firm based in Toronto and LA. I asked her to walk me through seven prominent architectural styles in Canada, how to recognize them, what their distinctive features are, and to point out some of her favourite Canadian examples. Check out her picks, plus some additional examples from across the country and see if you can put your skills to the test next time you’re out and about.

Neo-Romanesque

Romanesque revival architecture, popular in Canada in the 19th and early 20th centuries, harks back to the architecture of the 11th and 12th. Look for warm-feeling materials like etched stone and brick, low rounded arches, and recessed windows set back from the surface of the building. All of these help to give Neo-Romanesque buildings a heavy fortress-like feel, even though they also often have intricate decoration up close. It’s a style that works really well for civic buildings because of the sense of history and permanence it evokes.

Old City Hall, Toronto

Armstrong says: “Old City Hall is one of my favourite examples of Romanesque Revival in Canada. On the one hand, it’s incredibly eclectic, including turrets, a clock tower, pilasters and arches ; there’s a lot going on here. Yet all these elements feel unified as a whole, because the same material is used throughout. Also, it feels massive and heavy from a distance, but when you get up close, you notice an incredible level of detail, pattern, and texture etched onto that rich reddish-brown stone.”

Charlottetown City Hall, PEI

This has a similar feel to Toronto city hall, but the bigger window openings make it feel less fortified and lighter than really classic Romanesque building.

Windsor Station Montreal

Built in the late 1880’s, Windsor station served as the headquarters for the Canadian Pacific Railway, and was designated a national National Historic Site of Canada in 1975. Notice how the low rounded arches of the entrance give it a real heavy feel.

Neo-Gothic

You would never want to mistake Neo-Gothic architecture for Neo-Romanesque. Both old-timey styles recall the middle ages, but here is how to tell them apart. The original Gothic style came hundreds of years after original Romanesque, and Gothic architects used advances in building techniques to make bigger openings for doors and windows, high pointed arches, and steep sloping roofs. The effect is to make Gothic revival architecture feel much lighter and airier than Romanesque. If you’re at a loss, look at the arches: Romanesque = round, Gothic = pointy.

Notre-Dame Basilica, Montreal

Armstrong says: “Notre-Dame in Montreal is one of Canada’s most spectacular and early examples of Gothic Revival style architecture. It has lots of the classic Neo-Gothic elements: huge high arches at the entrance, expansive stained glass windows, grey stone. It was the largest church in North America at the time, and was soon imitated across Canada.”

Library of Parliament, Ottawa

This is a grand example of Gothic revival in Canada. In addition to the peaked arches, you have flying buttresses and a beautiful brightly lit cupula, which is great for reading.

St. Andrews Cathedral, Victoria

Built out of brick in 1890, St. Andrew’s Cathedral has been a National Historic Site of Canada since 1990. The soaring spire and large round windows are particularly of note. The vaulted ceilings inside are also breathtaking.

Art Deco

Whereas the revival styles above recall the past, Deco is all about the future (as seen from the 1920’s). “Art Deco” is named after the 1925 Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes in Paris. Armstrong told me that the whole style is a kind of celebration of the machine age: the shapes of trains, airplanes, and cars of the time served as inspiration to architects. Think Dick Tracy or The Rocketeer. Sleek curved lines and smooth surfaces are Deco trademarks. While they are less decorated on the exterior, Art Deco buildings often house lush interiors built of luxurious marbles and wood.

Cormier House, Montreal

Armstrong says: “This is a fabulous example of Deco in Canada. It was built by the Canadian architect Ernest Cormier as his own private residence in Montreal, and was later bought by Pierre Trudeau as a retirement home. It has a fairly austere facade which gives onto a classic Deco interior including lots of marble, shiny steel railings and pattern inlays on the floors. It’s like walking into a really swish speakeasy.”

Lawren Harris House, Toronto

This Forrest Hill home was designed by Alexandra Biriukova for Group of Seven artist Lawren Harris. It’s a combination of Art Deco design–notice the smooth stucco exterior–and Canadian details, like the pine needle motif on the balcony railings.

National Steel Car Entrance, Hamilton

This little-known building remains a bit of a mystery, but is still textbook Deco.

International Style

International Style is probably what you think of when you hear “modern architecture”. Slogans include “form follows function” (Louis Sullivan), “ornament is crime” (after Adolf Loos’s essay “Ornament and Crime”) and “a house is a machine for living” (Le Corbusier). The idea was to strip away all the superfluous decoration, complex etchings, and rococo flourishes of earlier architecture and make buildings that proudly flaunt their utilitarian nature.

Visually, you can recognize the international style by it’s boxy structure and emphasis on clear horizontal lines and grids. Floor-to-ceiling windows are another signature touch, as are buildings that are elevated on columns at street level. While the style was developed on a smaller scale for houses, it really took off when it was adopted for skyscrapers. In fact, if you are looking at a skyscraper, there’s a good chance you’re looking at an example of International Style architecture.

People who love it say it’s honest, economical, and shows a harmony of form and function. Those who don’t tend to think it’s boring, perhaps because it became so overwhelmingly popular.

TD Centre, Toronto

Armstrong says: “Mies (architects always refer to Mies van der Rohe by his first name) was a pioneer of modern architecture and his TD plaza is a masterpiece of International Style. It’s a very ordered design including two dark, elegant towers, a low pavilion and stone plaza. The sleek black steel and glass exterior makes a gorgeous contrast with a warm interior of creamy stone and wood. Floor-to-ceiling glass and a raised ground floor offer unobstructed views into the building and out to the city, breaking down the barriers between indoors and out. That’s a signature move of the international style as compared to, say, Neo-Romanesque style which really lets you know when you’re inside.”

Hamilton City Hall

As Hamilton’s official city architect in the 1950’s, Stanley Roscoe is responsible for much of the town’s civic architecture, including City Hall.

50 Park Road, Toronto

This former headquarters of the Ontario Association of Architects is a great small-scale example of International Style. Designed by John C. Parkin in the 1950s, the Toronto Star called it one of the five most influential buildings on TOronto. It is now home to DTAH, an architecture firm.

Brutalism

Brutalism gets its name from béton brut (raw concrete), not because it looks brutal, though we’d forgive the mistake. Like the International Style, Brutalism prizes honesty, utility, and eschews ornamentation. But it’s effect is utterly different. It’s a heavy, monumental, sculptural rebellion against the airiness of the International Style. It uses rough raw building materials that remain dramatically on display in the final product. Along with Post-Modernism, Brutalism is one of the most divisive architectural styles. In other words, a lot of people hate it. That’s a pity because Canada is home to some world-class specimens.

222 Jarvis St., Toronto

Armstrong says: “The old Sears headquarters is a little-known Brutalist gem, and one of my favourites. I’ve written about it before, in the AAmp blog. It’s a ten-story inverted pyramid made of a warm purple-bronze brick. Poured concrete is more typical of brutalist architecture, but there’s no mistaking the style. I love the imposing and confrontational shape combined with meticulous detailing that you can see up close. All in all, it’s a refreshing contrast to all the glass condos that are starting to dominate Toronto.”

Habitat 67, Montreal

Armstrong says: Built for Montreal’s Expo ’67, Habitat is (Israeli-Canadian architect) Moshe Safdie’s vision of a new, radical, housing future. He took modular, cubic, concrete “dwelling units”, and stacked and assembled them into a whole village of internal passages and outdoor gardens. It’s wonderful how this project blurs the line between a building and an organic, landscape formation.

Public Safety Building, Winnipeg

Heavy, repetitive, and grey, the Winnipeg Public Safety Building is just what people love and hate about brutalism.

Postmodernism

Like Brutalism, postmodernism has attracted its share of haters. Think of it as a reaction to the impersonal austerity of the International Style. You can think of postmodern architecture as a mashup that pulls together disparate motifs, elements, and materials: a clock tower here, a pediment there, rotundas everywhere. If Canadian superstar Frank Gehry is involved, you might even see a giant pair of binoculars. Some people think it feels contrived or chaotic, but others love how the familiar architectural elements are reappropriated in playful new ways.

Mississauga Civic Centre

Armstrong says: “Mississauga city hall, built in 1987, is one of the most prominent examples of post-modern architecture in Canada. It combines iconic elements of classical architecture (the symmetrical plan, giant pediment, rotunda) with references to Mississauga’s farm heritage. The cylindrical council chamber evokes a grain silo, the main building a farmhouse, and the clock tower is a windmill.”

1000 de la Gauchetière, Montreal

Built in 1992, this montreal skyscraper is a postmodern classic. The triangular copper roof and rotundas at the entrances are classic postmodern elements, as well as references to surrounding buildings.

Vancouver Library Square

Another Moshe Safdie design, the library square in Vancouver combines a Colosseum-like shape, glass-roofed concourse, and a rooftop park.

Emerging

Plenty of really interesting Canadian architecture is too new or too unlike anything else to be fit neatly into an established style. I had to limit Armstrong to three examples of new and emerging Canadian architecture that we shouldn’t miss.

Integral House, Toronto

Armstrong says: “Designed by Shim-Sutcliffe Architects, this experimental house is nestled in the ravines of north toronto, and was designed for a mathematician. Built of stepped curved walls of vertical oak fins and frosted channel glass – it blends seamlessly with the contours of the landscape. It also has a room for musical performance (the client was a violinist as well).”

Museum of History

Douglas Cardinal Architect

Armstrong says: “Edmonton-based architect, Douglas Cardinal, has a really distinctive architectural voice – his work is really sculptural and organic – with flowing, curvilinear walls and shell-like forms. The Canadian Museum of History, while not a new building – is a perfect example of this. It feels like more of a landscape formation than a typical building.”

Sluice Point House, Yarmouth County

Armstrong says: “One of Canada’s leading young architects, Omar Gandhi is known for really beautifully detailed, minimalist residences. This house on the coast of Nova Scotia is a great example. On the outside, the faceted roof and walls are clad in grey cedar shingles with large expanses of glass to capture dramatic views of the ocean. On the inside, Gandhi also sticks to one main material – wood again – but this time in a warmer tone that is supposed to reflect the area’s shipbuilding past. It’s a nice contrast with the stark white-grey exterior.”